When writing about a bad guy, I’ve stated before, you must make him realistic. He must be lovable, as well as hatable. He must have qualities, or goals, that are noble, and worthy of praise.

When writing about a bad guy, I’ve stated before, you must make him realistic. He must be lovable, as well as hatable. He must have qualities, or goals, that are noble, and worthy of praise.

J. Edgar Hoover was exactly such a man. He was a fine, upstanding citizen, raised in the early twentieth century. His goal was to organize, and run, an exceptionally efficient organization, known as the FBI.

Hoover was quite efficient in all of his ways. He discussed, with an advisor, that wanted criminals would have less of a chance of escape if he deputized more agents. Shortly thereafter Hoover developed the Ten Most Wanted list. Hoover’s desire to lower the odds for criminals translates to one of the best law enforcement agencies in the world. The FBI is also one of the most feared among gangs, the Mob, and the Mafia.

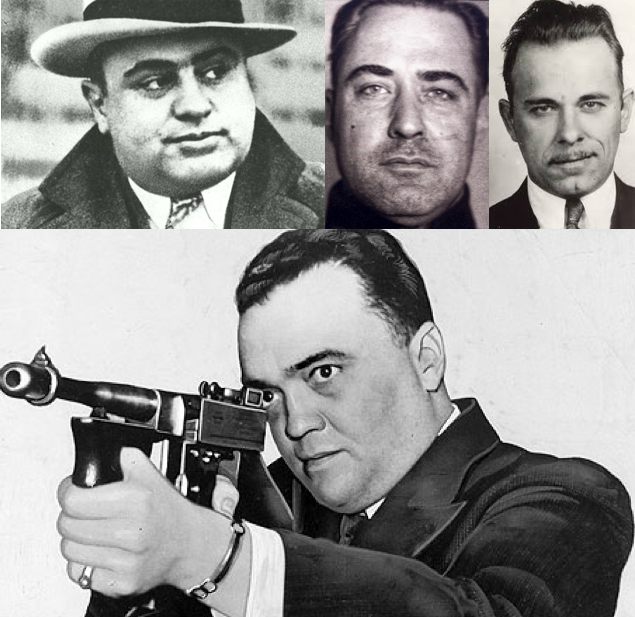

The start of Hoover’s problems (or the problems Hoover caused), was closely related to his beginning at the FBI. When he became the director, Hoover started throwing the bad guys in jail. To quickly summarize, Hoover was dealing with the most famous gangsters, killers, and kidnappers of his time. They were dealing with an organization that they thought was porous in its law keeping. Hoover surprised them, and they all went to jail. Hoover got his first taste of perfection, and victory.

He locked up Ma Barker and her boys, Herman, Lloyd, “Dock”, and Fred. Alvin “old creepy” Karpis joined them sometime around the late 1920s, and the early 1930s. Technically the FBI never locked up all of them, as most of them committed suicide before they could be captured.

Hoover also killed, or put away, “Pretty Boy” Floyd, “Baby Face” Nelson, John Dillinger, and Bruno Richard Hauptmann (Charles A. Lindbergh Jr. kidnapper.) “Machine Gun” Kelly, Al Capone. All of the famous bad guys.

During the Prohibition, Hoover and the FBI were quite active. Drinking is something that many people do, and the fact that it was illegal doubled if not tripled the number of drinkers. People like illegal things. (Not to mention, selling it to addicts would make any bootlegger a fortune.) Point is, there were a lot of shoot-outs, and since “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within… the United States… is hereby prohibited,” the FBI had a certain amount of jurisdiction, as the law was passed over the entire country. Thus making it federal law.

All of the success lead to the “G-Men”. No, not the New York Giants, but the Government Men. The name stuck, after a cornered “Machine Gun” Kelly reportedly cried out, “Don’t shoot, G-Men, don’t shoot!”

G-Men craze came in the form of children wearing G-Men pajamas, and playing with toy G-Men machine-guns. There was even a G-Men magazine, and subscribers of said magazine were taught how to get finger-prints using flour, and they were taught the G-Men secret whistle (two long, and one short).

During all of this Hoover developed his micro-management skills. He made sure that the FBI had a perfect reputation, and, most importantly, he made sure that the FBI got all of the big publicity cases. If Hoover knew one thing, it was how to play the system. Big publicity, equals free advertising. Hoover got the FBI’s MO out through the newspapers, and he didn’t have to pay. The MO was “We’re large, and we’re in charge.” It struck fear in the hearts of small crime-fighting operations, and criminals alike.

During the cold war, Hoover was definitely an anti-communism guy. Another one of the good/bad sides of him. He hated communism… so much that he was radically against it. When President Harry S. Truman signed the Executive Order 9835, in March, 1947, I can see Hoover dancing a jig with sheer glee.

The Executive Order initiated the Federal Employees Loyalty and Security Program. It applied to all two million federal workers. Anyone who was believed disloyal could no longer work for the federal government, although the term “disloyal” was never defined. Any employee could be dismissed, and any applicant turned down if there were “reasonable grounds for belief that a person is disloyal.” (This is the type of power that the Founding Fathers did NOT want the government to have.)

Keep in mind that during the cold war, the entire country was commie happy. Everyone was a communist if they did anything out of the ordinary. You were a commie if you sat at the same table every time at the local diner. You were a commie if you sat a different table every time.

The FBI investigated 14,000 employees, on the aforementioned grounds, and J. Edgar Hoover still wasn’t happy. He described communism as a disease that the USA needed to constantly guard against. With Executive Order 9835’s wording leaving everything to interpretation, Hoover was able to place wiretaps in peoples phones and such, if there was even a bit of suspicion.

“Mr. Hoover, sir, there’s this one guy who doesn’t look like a commie, doesn’t act like a commie, doesn’t eat like a commie, doesn’t talk like a commie–”

“Say no more,” Hoover would reply. “Wiretap his house, just in case.”

Hoover’s critics would constantly cite the small number of communists in the USA. Hoover would always reply, “It took only twenty-three men to overthrow Russia.” He obviously believed it could happen here.

That was one example of Hoover’s over-reaching paranoia. Hoover was good friends with Senator Joe McCarthy. Go figure. McCarthy was one of the worst kidney-punching sleazeball ever. He developed a low-blow type of politics. It’s called McCarthyism, defined as, “the practice of making accusations of disloyalty, especially of pro-communist activities, often unsupported or based on doubtful evidence.”

Point being, Hoover, and McCarthy, were both insanely against communism. Problem was that they both used the issue to investigate or eradicate political enemies, or anyone they deemed pee-pee ants.

Hoover was doing the wrong things, but for the right cause. It’s the ultimate bad/good, good/bad struggle that every author wants for his antagonists. Unfortunately for you, my tired reader, there’s more.

Bye for now,

Ian, the writer soon to be searching for a book, or several articles on concise writing.